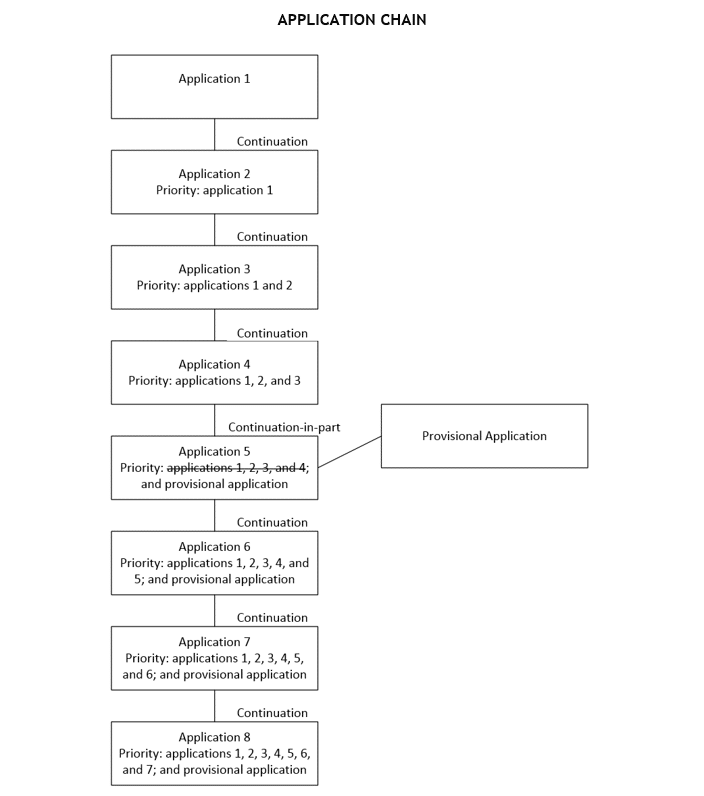

Data Engine Technologies LLC v. Google LLC, 2017-1135 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 9, 2018) is an appeal from the district court for the District of Delaware (No. 1:14-cv-01115-LPS). The district court held that the asserted claims of Data Engine Technologies’ (DET) US patents are ineligible under 35 USC §101. This decision was based on finding that the asserted claims are directed to abstract ideas and fail to provide an inventive concept.

The patents at issue are U.S. Patent Nos. are 5,590,259; 5,784,545; 6,282,551; and 5,303,146. The first three patents (referred to herein as “the Tab Patents”) are directed to electronic spreadsheets with tabs used to identify the spreadsheets and navigate between the spreadsheets. The fourth patent (referred to herein as “the ‘146 patent”) is directed to identifying changes to spreadsheets. This case law study analyzes the decision made by the court regarding the Tab Patents.

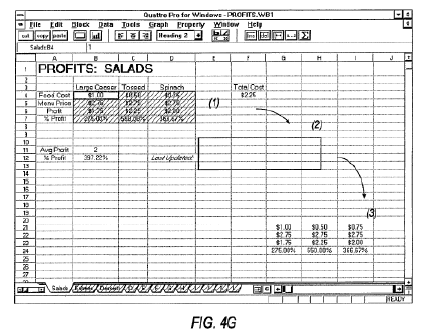

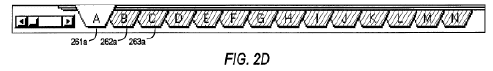

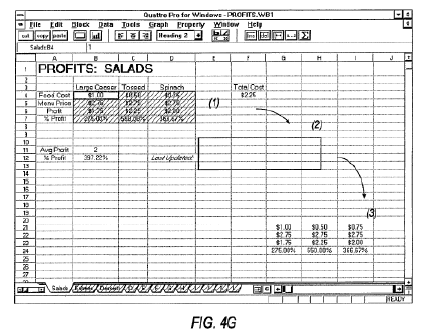

The Tab Patents are titled “Systems and Methods for Improved Spreadsheet Interface With User-Familiar Objects” and share a substantially common specification. The Tab Patents describe a three-dimensional, electronic spreadsheet:

that includes a number of tabs to navigate through different two-dimensional matrices of the spreadsheet:

where each of the tabs include identifiers that enable access to information on the respective spreadsheets.

The Tab Patents describe the tabs as familiar, user-friendly interface objects to navigate through spreadsheets while circumventing arduous process of searching for, memorizing, and entering complex commands. Accordingly, the Tab Patents present the tabs as a solution to problems that users had 25 years ago when navigating through complex spreadsheets, finding commands associated with the spreadsheets, manipulating the spreadsheets, etc. Several articles associated with Quattro Pro (the commercial embodiment based on the claimed method and systems) were published that touted the usefulness of the technology in the Tab Patents.

DET filed suit against Google, asserting claims from the Tab Patents. The district court considered claim 12 of the ‘259 patent as representative of all asserted claims of the Tab Patents. Claim 12 of the ‘259 patent included the following features:

while displaying [a] first spreadsheet page, displaying a row of spreadsheet page identifiers along one side of said first spreadsheet page, each said spreadsheet page identifier being displayed as an image of a notebook tab on said screen display and indicating a single respective spreadsheet page, wherein at least one spreadsheet page identifier of said displayed row of spreadsheet page identifiers comprises at least one user-settable identifying character.

Google filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c), arguing that the asserted claims of the Tab Patents are directed to patent-ineligible subject matter under § 101. The district court granted the motion with respect to the Tab Patents, concluding that representative claim 12 is “directed to the abstract idea of using notebook-type tabs to label and organize spreadsheets” and that claim 12 “is directed to an abstract idea that humans have commonly performed entirely in their minds, with the aid of columnar pads and writing instruments.” Further, the district court did not find that any features of claim 12 recited an inventive concept.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the Court) analyzed whether the Tab Patents are patent eligible under §101 according to the two-step test of Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International (“the Alice test”). In performing this analysis, the Court performed a de novo review of the Tab Patents and the evidence (including the articles about Quattro Pro) submitted to the district court.

The Court disagreed with Google, except with respect to claim 1 of the ‘551 patent. Claim 1 of the ‘551 patent recites:

In an electronic spreadsheet for processing alphanumeric information, said […] electronic spreadsheet comprising a three-dimensional spreadsheet operative in a digital computer and including a plurality of cells for entering data and formulas, a method for organizing the three-dimensional spreadsheet comprising:

partitioning said plurality of cells into a plurality of two-dimensional cell matrices so that each of the two-dimensional cell matrices can be presented to a user as a spreadsheet page;

associating each of the cell matrices with a user-settable page identifier which serves as a unique identifier for said each cell matrix;

creating in a first cell of a first page at least one formula referencing a second cell of a second page said formula including the user-settable page identifier for the second page; and

storing said first and second pages of the plurality of cell matrices such that they appear to the user as being stored within a single file.

Note that claim 1 of the ‘551 patent does not include an “implementation of a notebook tab interface” as recited in representative claim 12 of the ‘259 patent.

In disagreeing with the district court and Google on representative claim 12 (and the remaining claims of the Tab Patents other than claim 1 of the ‘551 patent), the Court determined that claim 12 recites “a specific structure (i.e., notebook tabs) within a particular spreadsheet display that performs a specific function (i.e., navigating within a three-dimensional spreadsheet).” The Court asserted that claim 12 claims a particular manner of navigating three-dimensional spreadsheets, implementing an improvement in electronic spreadsheet functionality. The Court frequently referred to the benefits described in the specification with respect to navigating through the spreadsheets. For example, the Court identified that claim 12 recited a structure that enables a user to avoid “the burdensome task of navigating through spreadsheets in separate windows using arbitrary commands.”

Further, the Court rejected Google’s notion that the claims merely cite “long-used tabs to organize information” and that such tabs are common in physical notebooks, binders, file folders, etc. The Court stated that it is not enough to simply point to a real-world analogy of the electronic spreadsheet because eligibility is not based on such concerns. Notably, the court acknowledged that those concerns are reserved for §102 and §103. As such, the Court determined that claim 12 was not directed to an abstract idea, and thus was patent eligible according to step 1 of the Alice test.

On the other hand, during review of claim 1 of the ‘551 patent, the Court concluded, under step 1 of Alice test, that the above claim is directed to the abstract idea of “identifying and storing electronic spreadsheets.” As mentioned above, claim 1 does not recite the notebook tab structure, but simply “associating each of the cell matrices with a user-settable page identifier which serves as a unique identifier for said each cell matrix.” The Court concluded that claim 1 of the ‘551 patent does not recite the specific implementation of a notebook tab interface. Furthermore, the Court concluded under step 2 of the Alice test that the additional features did not provide an inventive concept as the claim merely recites “partitioning cells to be presented as a spreadsheet, referencing in one cell of a page a formula referencing a second page, and saving the pages such that they appear as being stored as one file.”

This case provides a few practice insights for practitioners with a noticeable compare/contrast result between claim 12 of the ‘259 patent and claim 1 of the ‘551 patent. First of all, it is important to identify any functionality that a particular feature of a claim may have. Though an “identifier” may “identify,” such a feature is considered abstract. The identifier in the Tab Patents included the function of enabling navigation between the tabs and reference to other information in spreadsheets associated with the tabs. Including that functionality likely would have swayed the court to find the ‘551 patent eligible as well. Additionally, the Court frequently referred to the benefits of the tabs. These benefits included removing burdens on the user. As such, it obviously would not hurt to acknowledge such benefits when preparing patent applications. Best practices would also involve including and/or discussing any technical benefits that the tabs may have provided. For example, among other technical benefits, the tabs may have conserved processing resources associated with navigating to other spreadsheets by enabling a single click of the tab, rather than navigating multiple clicks through menus and/or windows to reach other spreadsheets.

Download Data Engine Technologies LLC v. Google LLC