Product Success Can Show Nonobviousness

By Patrick Hansen, Associate

The U.S. Supreme Court’s KSR decision has left an impression that any claimed invention based on a combination of known, related features is likely obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103. The recent Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM, LLC (Fed. Cir. May 18, 2020) decision is a heartening reminder that is not always the case. In Fox Factory, the Federal Circuit affirmed a Board holding that claims 1-26 of U.S. Patent 9,291,250 (‘250 patent) are not unpatentable as obvious under Section 103. What makes this decision reassuring for patent owners and applicants is that the Federal Circuit upheld SRAM’s ‘250 patent based on objective indicia of nonobviousness (also known as secondary considerations).

Fox Factory and SRAM are bicycle competitors, and SRAM’s ‘250 patent is directed to a single chainring of a bicycle that does not switch a chain between multiple chainrings. The single chainring has teeth that fit more snugly into chain link spaces, and the single chainring (marketed as “X-Sync”) has been praised for retaining the chain in poor cycling conditions.

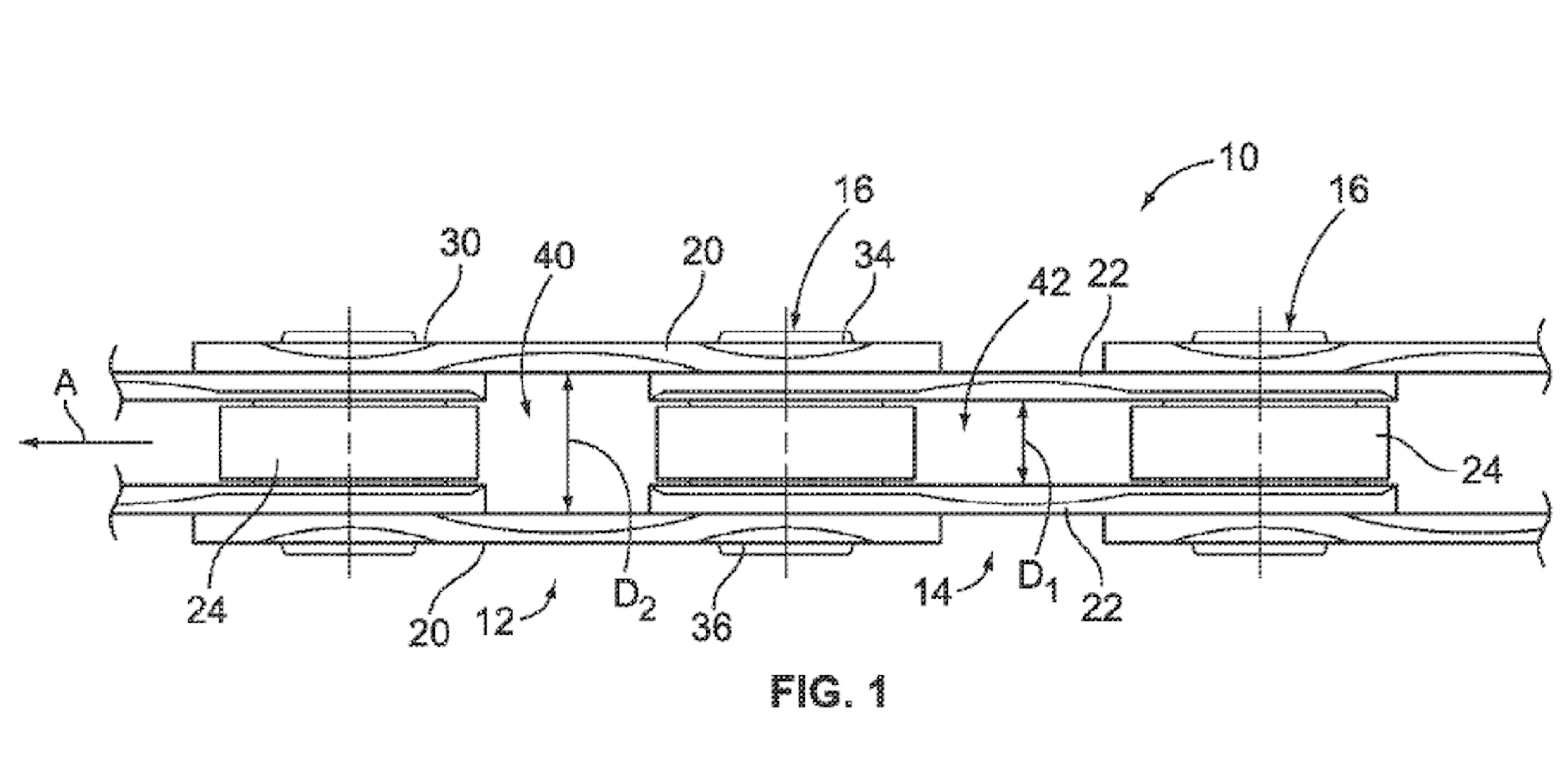

As shown in Fig. 1 from the ‘250 patent, link spaces alternate in size (D1 or D2) due to the manner in which pieces of a chain are linked. Claim 1 of the ‘250 patent recites a chainring with wider teeth of a first size that alternates with teeth of a second size, in order to snugly fit into respective outer (D2) and inner (D1) link spaces. In particular, claim 1 recites that a wider tooth is designed to fill, at the midpoint, at least 80% of an outer link space.

Claim 1 of the ‘250 patent recites a chainring with wider teeth of a first size that alternates with teeth of a second size, in order to snugly fit into respective outer (D2) and inner (D1) link spaces. In particular, claim 1 recites that a wider tooth is designed to fill, at the midpoint, at least 80% of an outer link space.

SRAM asserted the ‘250 patent against Fox Factory in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. In a corresponding inter partes review (IPR) proceeding, Fox Factory cited Japanese patent publication JP S56-42489 (“Shimano”) and U.S. Patent 3,375,022 (“Hattan”). Shimano describes a chainring with widened teeth for wider link spaces, and Hattan describes filling link spaces between 74.6% and 96% of a space width at the bottom of a tooth. Fox Factory argued that it would have been obvious to a skilled artisan to see the utility in designing a chainring with widened teeth to improve chain retention and to look to Hattan for filling the link space at least 80%. However, the Board found that Hattan’s fill percentages applied to the bottom of a tooth rather than the midpoint of the tooth. Notably, the Board found that SRAM’s evidence of secondary considerations rebutted Fox Factory’s argument that a skilled artisan would nevertheless find it obvious to modify Shimano’s chainring teeth to fill at least 80% of a wide link space at the middle of a tooth. Judge Lourie, writing for the Federal Circuit panel that included Judges Mayer and Wallach, affirmed the Board’s decision.

As you may recall, the Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966) analysis includes four factors: (1) the scope and content of the prior art; (2) the differences between the prior art and the patent claims; (3) the level of ordinary skill in the art; and (4) secondary considerations (also known more favorably as objective indicia of nonobviousness). All four factors are to be evaluated collectively before a conclusion on obviousness is reached, and the burden of proof remains with the patent challenger. Fox Factory argued that the only difference at issue is the degree to which a wider link space is filled, measured halfway up the tooth. Fox Factory also argued that the Board erred in presuming a nexus between the claimed invention and evidence of success, arguing that it is the tall hooked teeth that drove the X-Sync chainring to be successful.

While acknowledging that a mere change in proportion may not meet the level of invention required by Section 103, the Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that SRAM’s design of the X-Sync chainring teeth, as claimed, displayed significant invention. The X-Sync chainring’s success surprised skilled artisans who were skeptical about it solving the long-felt need of chain retention. In fact, the industry awarded the X-Sync chainring “Innovation of the Year.”

The Federal Circuit found that the X-Sync chainring and the ‘250 claims met the nexus requirement – that a product from which the secondary considerations arose is “co-extensive” with the claimed invention. The Federal Circuit also stated that the unclaimed features, such as the hooks and protrusions of the teeth, are to some extent incorporated into the >80% fill requirement. The Federal Circuit concluded that substantial evidence supports the Board’s determination that a nexus exists between the X-Sync chainring’s success and the teeth profile that is essentially the claimed invention.

While Fox Factory does not present any new rule, it is a reminder that patent owners and applicants should keep records indicating a long-felt need and any industry skepticism, as well as records of subsequent success of a product to which claims are directed. Claim drafters should learn from inventors which features could contribute to a product’s commercial success or acclamation. Fox Factory reassures us that objective indicia of nonobviousness can still be a meaningful consideration at the Board and the Federal Circuit, even over what may be argued to be routine optimization.